At Christmas we celebrate the advent of our Lord, the mystery of Incarnation of the Son of God. For those of us with a theological bent, it raises a question that theologians have asked for centuries: if not for sin, would the Son have become incarnate anyways? Or, is the Incarnation the central act of salvation or the Passion? Christ’s birth or Christ’s death? Which is logically prior? Obviously they’re both important, but the way you answer this question has implications for other doctrines down the line and there are good arguments on both sides.

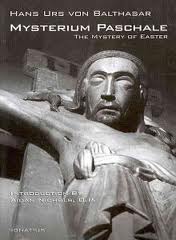

Catholic giant Hans Urs Von Balthasar addressed this question in one of the most fascinating atonement theologies of the 20th century, his Mysterium Paschale: The Mystery of Easter, a meditation on the Triduum Mortis, the three days of Christ’s atonement: Good Friday, Holy Saturday, and Resurrection Sunday. Honestly, even though I’m not sure I can go for his controversial theology of Holy Saturday, brilliant though it is, most Evangelicals could stand to read his section on Good Friday–it’s worth the price of the book alone.

Catholic giant Hans Urs Von Balthasar addressed this question in one of the most fascinating atonement theologies of the 20th century, his Mysterium Paschale: The Mystery of Easter, a meditation on the Triduum Mortis, the three days of Christ’s atonement: Good Friday, Holy Saturday, and Resurrection Sunday. Honestly, even though I’m not sure I can go for his controversial theology of Holy Saturday, brilliant though it is, most Evangelicals could stand to read his section on Good Friday–it’s worth the price of the book alone.

Before getting to the treatment of the three days, Balthasar argues that the Incarnation is clearly ordered to the Passion and that most attempts to reconcile the two trains of thought are misguided. Yet, the same time, if we look deeply into the Scriptures, the tradition, and the deeper theological logic, we will see that:

…to focus the Incarnation on the Passion enables both theories to reach a point where the mind is flooded by the same perfect thought: in serving, in washing the feet of his creatures, God reveals himself even in that which is most intimately divine in him, and manifests his supreme glory. (pg. 11)

East and West

Balthasar’s biblical arguments and later theological elucidation are both fascinating and convincing. The section that was most eye-opening for me in reading it a few years ago, was his section on the testimony of the tradition, both East and West on this subject matter.

Typically we are told that in the Orthodox East, a greater emphasis was laid on the Incarnation and that the Passion is accidental within the scheme, while the Latin West has placed a greater emphasis on the death on the Cross and so subordinates the Incarnation. Balthasar argues that this is a mischaracterization for “There can surely be no theological assertion in which East and West are so united as the statement that the Incarnation happened for the sake of man’s redemption on the Cross.” (pg. 20) Since this is somewhat uncontroversial of the West, specifically of the East he highlights that in their main theory, “the assuming of an individual taken from humanity as a whole…affects and sanctifies the latter in its totality, except in relation with the entire economy of the divine redemptive work. To ‘take on manhood’ means in fact to assume its concrete destiny with all that entails—suffering, death, hell—in solidarity with every human being.” (ibid.)

The Consensus

He then goes on to substantiate his claim with more citations from the Fathers than I have space to quote here; a number of them in Latin and Greek. I will reproduce only a few:

Athanasius—

The Logos, who in himself could not die, accepted a body capable of death, so as to sacrifice it as his own for all.

The passionless Logos bore a body in himself…so as to take upon himself what is ours and offer it in sacrifice…so that the whole man might obtain salvation.

Gregory of Nyssa—

If one examines this mystery, one will prefer to say, not that his death was a consequence of his birth, but that the birth was undertaken so that he could die.

Hippolytus—

To be considered as like ourselves, he took upon him pain; he wanted to hunger, thirst, sleep; not to refuse suffering; to be obedient unto death; to rise again in a visible manner. In all this, he offered his humanity as the first-fruits.

Hilary—

In (all) the rest, the set of the Father’s will already shows itself the virgin, the birth, a body; and after that, a Cross, death, the underworld—our salvation.

Maximus Confessor—

The mystery of the Incarnation of the Word contains, as in a synthesis, the interpretation of all the enigmas and figures of Scripture, as well as the meaning of all material and spiritual creatures. But whoever knows the mystery of the Cross and the burial, that person knows the real reasons, logoi, for all these realities. Whoever lastly, penetrates the hidden power of the Resurrection, discovers the final end for which God created everything from the beginning.

Again, I have left out various citations by figures such as Irenaeus, Tertullian, Ambrose, Gregory Nazianzen, Cyril of Alexandria, Leo the Great, Augustine, and others (pp. 20-22). Still, as Balthasar notes, “These texts show…that the Incarnation is ordered to the Cross as its goal. They make a clean sweep of that widely disseminated myth” that the Greek Fathers, against the Latins, are focused on the Incarnation to the exclusion of the Cross. (pg. 22)

The Crib leads to the Cross

The Crib leads to the Cross

As interesting of a conclusion as this is for the history of theology, “more profoundly” says Balthasar, “the texts offered here also demonstrate that he who says Incarnation, also says Cross.” (pg. 22) Of course this should come as no surprise. In all these texts the Fathers were only repeating the apostles, “But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons” (Gal. 4:4-5), and our Lord himself who said, “And what shall I say? ‘Father, save me from this hour’? But for this purpose I have come to this hour.” (John 12:27)

As we look to the Crib, we must see the Cross in the background—both holding our Savior in his weakness and humility—the peaceful beginning pointing the agonizing end suffered for our sakes; the cries from the cradle foreshadowing the cries from the Cross. This Christmas, as we gather around to celebrate the mystery of Incarnation, we cannot forget the Passion.

Soli Deo Gloria

Have “perused” the book, but will take a deeper look. THANKS!

(Merry Christmas to You and Yours!)

Merry Christmas to you as well!! Enjoy the book. It’s well worth the time.

Oh come on. Can’t you Calvinists let him be a baby for one day? 😉

I’m trying to figure out how to articulate the intuitive uneasiness that I have. I think I just hate any form of reductionism to the gospel for aesthetic reasons. “He was born to die” sounds very reductionist; it’s like a song with only one chord. I’m very resistant to anything that feels like it turns Jesus into a mathematical formula that solves a cosmic equation. I just don’t want us to sidestep the scandal of an incarnate God who pooped and peed on Himself for the first probably two years of His life. Gregory of Naziansus says, “That which He did not assume, He cannot redeem.” There’s a side to the incarnation that isn’t strictly about fulfilling the demands of God’s justice bankers. For Him to be “God with us” and the messiah of the Jewish people says to me solidarity. For people who don’t live in privilege, the fact that God came as a poor kid is significant. I’m very uneasy about dismissing everything that the liberation theologians have to say about the solidarity of Jesus’ incarnation, because I’m troubled by the way that the theology of the privileged seems to be self-validating.

It seems like we should notice a significance to the fact that atonement takes the form of incarnational solidarity. Anselmian mathematics notwithstanding, couldn’t God have found some other way to bridge the gap, pay the debt, etc? For Him to do it through incarnation means that He comes down and reaches out rather than just sitting on His throne with His arms folded like a Xerxes waiting to see who figures out the special dance that we need to do to be accepted into His harem. So instead of saying “Jesus was born in order to die,” I would say, “God chose to redeem the world by making His Word flesh.” That way the incarnation doesn’t get immediately swallowed up by something else. That way it can be Christmas for a day even if it’s Good Friday and Easter every other day.

“Born to die” can be reductionistic but it does not have to be. It’s a great, beautiful chord set within a larger song, that ought to be pointed out to be appreciated as part of the whole. (Also, if you look at the other quotes, the thread usually is set within a larger fabric.) I don’t think this side- steps the scandal, but gives it real life—that peeing, pooping baby has cosmic purpose and significance. The salvation of humankind begins here, with an infant. It stops us from sentimentalizing Christmas into this generalized celebration of the American family, but reminds us that Christ came to save us.

Also, I think Christ’s solidarity with the poor is a great point to make. I really don’t know how pointing forward to the Cross negates that. In fact, I think it beefs it up by pointing out that the Savior of the world, the hero of it all, comes from the poor part of town. So, that’s a bit of a non-sequitur. Also, identifying liberation theology with THE theology of the non-privileged is a bit misleading. The underprivileged, the poor, the downcast need a savior for their bodies, yes, but they are souls too, created, sinful, broken, guilty, and in need of redemption just as much as the consumeristic privileged congregations we deal with. I think we do them a disservice to think they’re only concerned with these things.

As for the question, “couldn’t God have found some other way to bridge the gap, pay the debt, etc.?” Yes, and no. As to the historical particulars, probably. As to the redeeming death and resurrection, no. To say otherwise throws us into the nominalism/voluntarism where God could have done it otherwise, but for some reason he picked the bloody version.

I’m fine with Christmas being Christmas. But I think the Cross is inherently part of the meaning of Christmas.

A blog where you quote Balthazar & the Fathers. (*slow clap*) Thanks for this! I wonder about the origin of the false dichotomy of “incarnation vs passion”. I certainly haven’t encountered this in my readings of current eastern orthodox theologians, or in my reading of the Fathers. I’ve always interpreted the writings as:

The atonement is occurring in the Incarnation, and penultimately in the death of Christ & ultimately in the resurrection. [cf. 1 Cor 15:14] The Cross reveals what was always taking place in the Incarnation…or something like that.

[sidenote: One of my criticisms of “Locating Atonement” was the absence of a dedicated section on the incarnation]

As Reader Irenaeus puts it,

“Christ identifies fully with humanity through the incarnation. He stands in solidarity with us from birth to death. The atonement does not begin or end with the Cross. Christ’s reconciling work is initiated throughout his life and ministry, declaring that God’s table is open to fellowship for all who will come (even before the Cross) and that forgiveness, healing, and deliverance (not just provisionally pending his death but actually as we come) are available to all who believe.”

Similarly Dr. Kharalambos Anstall writes,

“‘The Word became flesh’-The dark shadow of death is driven away by a new effulgence of uncreated light. All of creation, formerly submerged since the Fall in a black slough of despondence, rouses and shakes itself in the warmth and golden illumination of a new beginning- a virtual regeneration of life through loving communion with God….

Only by His incarnation as the second Person of the Holy Trinity, wherein He “put on the flesh” of humanity while still God, could he overcome human mortality, defeating death by (His) death in a single, magnificent display of co-suffering love. In Christ, the Expected One has come, the Anointed One, the Messiah of Israel: “the Word made flesh” , Word who, in the beginning, “was with God and was God.” And, through His glorious Resurrection, He extended the potential for eternal life to all of humanity.”

Dr. Ben Myers explains this VERY well in this video:

Hi Derek,

Not sure when you wrote this article. But I appreciate it. My name is Paul Haroutunian, also a graduate of TEDS. Had VanHoozer, his first year of teaching systematic theology at TEDS in 1986!