The cross of Christ has always been a scandal and an offense. As a symbol of social shame in the Greco-Roman world, the idea of a Crucified God elicited scorn from the cultured elites. For 1st Century Jews, a crucified Messiah was a nonsensical contradiction in terms. Even today, speaking of Jesus’ death as the saving center of history provokes a quizzical response both in the pews and the marketplace. Beyond that, there has been a wide variety of debate around just how Jesus’ death saves us within the church itself. Historically, there has been no binding ecumenical statement on the issue comparable to those on of the Trinity and the person of Christ. The result is that many different approaches to explaining the way the death Christ exercises a saving function in the economy of the Triune God.

The cross of Christ has always been a scandal and an offense. As a symbol of social shame in the Greco-Roman world, the idea of a Crucified God elicited scorn from the cultured elites. For 1st Century Jews, a crucified Messiah was a nonsensical contradiction in terms. Even today, speaking of Jesus’ death as the saving center of history provokes a quizzical response both in the pews and the marketplace. Beyond that, there has been a wide variety of debate around just how Jesus’ death saves us within the church itself. Historically, there has been no binding ecumenical statement on the issue comparable to those on of the Trinity and the person of Christ. The result is that many different approaches to explaining the way the death Christ exercises a saving function in the economy of the Triune God.

Though widely-held by Evangelicals and Protestants of all stripes (and seemingly even some Catholics like H.U Von Balthasar), among the most controversial views is that of “penal substitution” or “penal representation”, PSA for short (penal substitutionary atonement). At its heart, the idea is that Jesus’ death on the cross was the divine means of dealing and dispensing with the guilt incurred by sinners who have rebelled against the true God. Humanity through its sin violated the divine law, wrecking God’s intended shalom, bringing down condemnation upon them, and alienating them from proper relationship with God. God being just as well as loving and merciful sends the Son, Jesus, as an innocent, representative person, the Godman, to take responsibility for human sin and suffer punishment on behalf of sinners. Or rather, he suffers the legal consequences of sinners, the judgment and just wrath of God against sin, thereby relieving them of guilt, bringing about reconciliation. Roughly.

As with just about any idea in theology, there has been no little confusion around this issue, provoking a number of criticisms and responses over the years. Now, I happen to be convinced on the basis of Scripture that some form of penal substitution is at the heart of Jesus’ saving work on the cross. I thought it might be helpful, then, to have some sort of post dedicated to listing and answering most of the standard objections against the doctrine, as well as engaging some of the modern objections against it. Mind you, this post is not intended to be extensive in every sense. I will not and cannot go into detailed exegetical arguments establishing the doctrine according to a number of key texts, nor establishing the long-range biblical theology that undergirds it. I think the case is there, but I will point you to resources for that along the way and at the bottom of the post.

That said, I do want to engage some of the broadly theological objections against it, as well as correct popular caricatures of the doctrine along the way. I have to say that a number of the issues that people have with penal substitution are quite understandable when you consider some of the silliness that passes for biblical preaching on the subject in popular contexts. Those who affirm the doctrine as true and beautiful do our hearers no benefit when we defend misshapen, caricatured versions of the doctrine. I’ll try to do my best to avoid that in what follows.

First Principles

A few principles will serve to ground the rest of the discussion.

First, many problems arise when advocates treat penal substitution as a totalizing theory of atonement set against Christus Victor or moral influence, or some other kind of atoning action. Proponents all-too-often hold it up as “The One Atonement Theory To Rule Them All”, as one friend put it. Instead, I’ve already argued before that all of these “theories” are more properly seen as containing insights into various aspects and angles of one great work of atonement. I do think there is a place for ordering these elements logically, and penal substitution is something of a lynchpin here, but there is no excuse for downplaying or ignoring the other themes. For more on this, see here and here.

Second, one important principle to observe is that when it comes to theology “abuse does not forbid proper use.” In other words, because the doctrine has been misused in the past, that doesn’t mean it cannot be properly taught or deployed again. Virtually any can be and has been abused at some point. Growing up Evangelical, I’ve certainly seen distortions and caricatures of the doctrine. We should be prepared to find, though, despite the distortions, there is a properly biblical truth to be held on to here.

Well, with those caveats out of the way, let’s get to it, shall we?

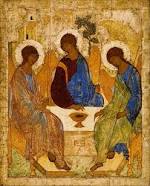

1. Critics often allege that penal substitution is anti-trinitarian in that it pits an angry Father punishing a loving Son, introducing a false split in the Godhead. While this can happen in popular preaching, when it comes to the tradition, this charge is manifestly false. Penal substitution is inherently trinitarian in that it follows the best Patristic pattern of thought in seeing atonement as the work of the whole Trinity. All trinitarian action begins with the Father, is accomplished through the Son, and perfected by the Spirit. In a properly-trinitarian PSA the Father hands over the Son, while the Son willingly offers himself up in obedience to the Father, and he does so through the empowering work of the Spirit. It is a costly work of love and sacrifice that posits no split purposes within the Godhead, for the Three being one God have one will.

Also, contrary to popular mischaracterizations, the Father never hates the Son, but always looks on the Son in love, even while the Son suffers the penal consequences of sin in place of sinners. Calvin says as much:

Yet we do not suggest that God was ever inimical or angry toward him. How could he be angry toward his beloved Son, “in whom his heart reposed” [cf. Matthew 3:17]? How could Christ by his intercession appease the Father toward others, if he were himself hateful to God? This is what we are saying: he bore the weight of divine severity, since he was “stricken and afflicted” [cf. Isaiah 53:5] by God’s hand, and experienced all the signs of a wrathful and avenging God. –Institutes, II.xvi.11

In fact, it is precisely because of the Son’s willingness to suffer on their behalf that the Father loves the Son (John 10:18). What’s more, classically, advocates of PSA have also held to divine simplicity, thereby ruling out tout court any thought of a split in the Godhead. All of the best exponents hold this up from Calvin all the way to J.I. Packer and John Stott. For more, see Thomas McCall’s excellent little book Forsaken on this.

2. Others charge that PSA has God directly “killing”Jesus. Alternatively, in another version, the charge is that if PSA is true, then the mobs who crucified Jesus were doing God’s will. There are a number of issues with these charges. The first, and most obvious, is that it rejects the appropriateness of distinguishing divine intention from human one. If God “wills” the death of Jesus in any sense, he is a killer, or murderer, or we have no room to say that the Romans were guilty of a crime because they were only doing God’s will at that point. However, biblical thought is not that cramped.

Instead, we are trained by Scripture to see God and humanity working at different levels with different aims at their own level of being. In other words, God’s being and activity is not “univocal” but “analogical” with ours. God is Creator and so he does not operate on the same level of being as we do. His purposes for history are different than ours, even in the same events of history. As Joseph tells his brothers of their sinful actions in selling him into slavery, “You intended it for evil, but God intended it for good.” God might will an action or an event for a good reason, concurring and allowing human actions, even while the humans perpetrating it are doing so for evil reasons that God does not share. This is sort of thing is common throughout the Old Testament. Various events of judgment such as the Exile at the hand of the Assyrians and Babylonians are both the wicked work of evil empires, all the while being God’s own judgment through them. It is clear from the biblical witness at numerous points that God intends Jesus’ (indeed his own!) death on the cross (John 12:27; Acts 2:23; 4:27-28). Most of the exegetical gymnastics at this point are simply astounding. To reject the cross as divinely-intended in some sense is to simply reject the witness of the Gospels, Paul, Hebrews, and Jesus himself who says that these things “must” (dei) happen to fulfill Scripture.

3. Related to the last claim, PSA has been infamously referred to as “Divine Child Abuse” and charged with encouraging victims of abuse, especially women, to identify with models of passive, redemptive suffering in imitation of the Son. Let me say at the outset, if there are people who have suffered under preaching that encourages women, children, or anyone else to passively suffer under the abuse of the violent, I am deeply sorry to hear this. This is a gross distortion of Christian doctrine that I strongly repudiate. Penal substitution properly preached does not encourage that kind of passive submission to abuse.

First, I would point out that the abuse the Son suffers is at human hands. The Father does not abuse the Son, though it is by God’s will that he suffers in this fashion. Remember that divine and human intentionality need to be distinguished here. Second, it also teaches that the Son’s work is uniquely redemptive. Moreover, this point is important. Not everything that God does in Christ is strictly imitable. You cannot create reality out of nothing. You cannot pour the Spirit out into creation. You are not the Eternal Son who is going save anyone by suffering that abuse. Your abuse is not atoning in the least bit. It is a sin against you and God is very angry with it. In fact, God’s judgment on the cross is a testimony to his judgment against abuse and injustice.

Still, there is a place for self-denial and cross-bearing in the Christian life. This is simply a matter of the biblical record and at the heart of Jesus’ own path of discipleship. However, with every piece of biblical insight, there needs to be careful, wise application. Paul tells us that we can serve Christ in whatever station we find ourselves in, but there’s nothing wrong with getting your freedom if you can (1 Cor. 7). There is nothing in PSA that requires us to passively endure abuse in imitation of Christ. What’s more, if anything, PSA properly though through ought to be deployed as a testimony of the non-selfish, sacrificial life of all, including men, or anyone else in authority ought to lead in their dealings with others.

Finally, and this is crucial, in PSA the Son is not some weak child subject to an all-dominating Father. He is the Eternal Son who willingly and authoritatively laid down his life, offering himself up through the Spirit. The Son is an active, willing adult. No one takes his life from him, but he lays it down willingly (Mk. 10:45; Lk. 23:46; John 10:11, 15, 17-18; 13:1; Gal. 2:20). He heroically gives up his life for others and is not simply a victim of violent forces beyond his control.

4. Classically, some have objected that PSA is morally repugnant because moral guilt is not transferable. It is wicked to punish the guilty in the place of the innocent. In response to this, some have noted that some forms of debt are transferable. People can pay off each other’s financial debts all the time. Why not Christ? Well, as long as it is thought of financially, yes, that seems unproblematic. But moral debt seems different and non-transferable. We are not usually supposed to punish the guilty in the place of the innocent. At this point, it seems that a few things ought to be made clear.

First, Jesus is the Christ, not just any other person. Christ is not just a name; it is a title meaning “Messiah”, the Anointed King. In the biblical way of thinking, kings of nations stood in a special representative relationship with their people. As N.T. Wright says, when you come to the phrase “In the Messiah” in the NT, then, you have to think “what is true of the King, was true of the people.” So, if the King won a victory, then so did the people, and so forth. The King was able to assume responsibility for the fate of a people in a way that no other person could. This is the underlying logic at work in the Bible text. We do not think this way because we are modern, hyper-individualists, but he is the one in whom his people are summed up.

Though sadly this gets left out of many popular accounts of PSA, this is actually what classic, Reformed covenant theology is about. Jesus occupies a unique moral space precisely as the mediator of the new covenant relationship. Most people cannot take responsibility for the guilt of others in such a way that they can discharge their obligations on their behalf. Jesus can because he is both God and Man, and the New Adam, who is forging a new relationship between humanity and God. This, incidentally, is just a variation on Irenaeus’ theology of recapitulation (re-headship). As all die in Adam, so all are given life in Christ (Rom. 5:12-20). If Christ dies a penal death for sins, then those who are in Christ die that death with him (2 Cor 5:14). His relationship is, as they say, sui generis, in its own category.

This is where modern, popular analogies drawn from the lawcourt fail us. We ought not to think of Christ dying to deal with the sins of people as some simple swap of any random innocent person for a bunch of guilty people. It is the death of the King who can legally represent his people in a unique, but appropriate fashion before the bar of God’s justice. He is our substitute because he is our representative. Strictly speaking there are no proper analogies, but there is a moral logic that is deeply rooted in the biblical narrative.

5. Some say that any idea of justice must not be retributive, but only restorative. It is repugnant to think that justice must include some tit for tat “balancing of the moral scales.” I would first point out that pitting retribution against restoration is a false dichotomy. Retribution has claims of its own alongside distributive and restorative concerns when it comes to a broader, holistic biblical account of justice. Theologians such as Miroslav Volf, Oliver O’Donovan, and Garry Williams have pointed out that in the biblical record, retribution is not merely about getting payment for a debt, but about naming evil. Judgment is about calling evil what it is, as well as giving it what it deserves. According to the Scriptures, a God who does not name evil, and does not treat it as it deserves is not good. Quite frankly, it is impossible to screen out any notion of retribution from the biblical account without simply chopping out verses and narrative wholesale.

Herman Bavinck establishes quite clearly the retributive principle in Scripture and worth quoting at length:

…retribution is the principle and standard of punishment throughout Scripture. There is no legislation in antiquity that so rigorously and repeatedly maintains the demand of justice as that of Israel. This comes out especially in the following three things: (1) the guilty person may by no means be considered innocent (Deut. 25:1; Prov. 17:15; 24:24; Isa. 5:23); (2) the righteous may not be condemned (Exod. 23:7; Deut. 25:1; Pss. 31:18; 34:21; 37:12; 94:21; Prov. 17:15; Isa. 5:23); and (3) the rights of the poor, the oppressed, the day laborer, the widow, and the orphan especially may not be perverted but, on the contrary, must be upheld for their protection and support (Exod. 22:21f.; Deut. 23:6; 24:14, 17; Prov. 22:22; Jer. 5:28; 22:3, 16; Ezek. 22:29; Zech. 7:10). In general, justice must be pursued both in and outside the courts (Deut. 16:20). All this is grounded in the fact that God is the God of justice and righteousness, who by no means clears the guilty, yet is merciful, gracious, and slow to anger, and upholds the rights of the poor and the afflicted, the widow and the orphan (Exod. 20:5–6; 34:6–7; Num. 14:18; Ps. 68:5; etc.). He, accordingly, threatens punishment for sin (Gen. 2:17; Deut. 27:15f.; Pss. 5:5; 11:5; 50:21; 94:10; Isa. 10:13–23; Rom. 1:18; 2:3; 6:21, 23; etc.) and determines the measure of the punishment by the nature of the offense. He repays everyone according to his or her deeds (Exod. 20:5–7; Deut. 7:9–10; 32:35; Ps. 62:12; Prov. 24:12; Isa. 35:4; Jer. 51:56; Matt. 16:27; Rom. 2:1–13; Heb. 10:30; Rev. 22:12).

–Reformed Dogmatics Volume 3: Sin and Salvation, pp. 162-163

For those interested in following up, it’s instructive to peruse Bavinck’s Scripture references, to see they are not merely proof-texts. Upon examination, one is struck by the massive amount of biblical material that has to be reinterpreted or shunted to the side in order to screen out the retributive principle. (Also, for those who have access, the entire section examining justice, retribution, and punishment is worthwhile.)

Also, it should be said here that the judgment of the cross is not simply about God matching up ounces of suffering according to some pecuniary punishment scale. It is about Jesus suffering the final, ultimate judgment of alienation on our behalf. Instead of thinking about it in terms of units of suffering matching up for sins, think of it in terms of total exile and alienation. Sin ultimately alienates and cuts us off from God in a total sense. We reject God and so in his judgment God names and answers our sin by handing us over to the fate we have chosen: exile from the source of all good, life, and joy, which is simply death and hell. This is what Jesus suffers on the cross on our behalf. He takes that situation of total alienation and damnation upon himself.

What’s more, retribution can be part of a broadly restorative aim. Christ’s penal death was not simply a strict act of retributive justice whose sole aim was to satisfy God’s wrath or a strict, economic tit for tat exchange of punishment for sin. God could have had that by simply leaving people in their sins so that they might pay out their just wages, death (Rom. 6:23a). Instead, God’s atoning act through the cross transcends strict retributive exchange, not by ignoring, but by fulfilling the claims of justice and pushing past them to the gift of God which is eternal life in Christ Jesus (Rom. 6:23b). God did not simply want to deal with sin; he wanted to save sinners. God did not only want to be vindicated as just, but instead wanted to be both “just and the justifier of one who has faith in Jesus” (Rom. 3:26). Wrath is dealt with to be sure, but it is dealt with in Christ in order to clear the path for the gift of the Spirit that enables believers to live new, reconciled lives now which will issue in the final total restoration through the gift of resurrection. “God pours himself out for us, not in an economic exchange, but in an excess of justice and love.” The gift of God far outweighs the trespass of man (Rom. 5:16). The penal, retributive justice of God has a more-than-retributive goal; it aims at the “restoration of community and eternal peace” with God and others. Peace happens through the gift of life in the Spirit, which is peace (Romans. 8:6). Thus, the retributive justice of God has a restorative goal which transcends strict, economic justice through his gift-giving grace which comes out only when developed in light of its Triune goal: the gift of the Spirit.

Finally, for those still struggling with the necessity of thinking in terms of retribution, I would direct your attention to C.S. Lewis’ classic essay, “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment.” Vintage Lewis, the discussion is still relevant to the issues addressed in this section.

6. From another angle, some charge that PSA encourages moral passivity. It is said that is no active ethic that can be derived from Jesus’ sin-bearing work on the cross. Indeed, it seems to mute it. There are a number of points to be mentioned here. First, we should question the idea that PSA even has to be justified on this account. We must not fall prey to the populist, pragmatic idea that for a doctrine to be true, it has to be immediately practical and imitable. As theologian Karen Kilby has pointed outwith respect to the doctrine of the Trinity, we do not need to be justifying our model of what God is like based on what kind of political programme it generates. We measure our account on the basis of what God has revealed of himself, not of what use he can be to us. The same thing is true for atonement. We affirm our understanding of atonement on the basis of Scripture, not simply because it is useful. What’s more, we have to remember that each doctrine has its place within the wider structure of Christian truth. Atonement is not the only doctrine in our toolkit for constructing our ethics. We get to work with a lot of truth. So the formal charge does not hold water.

All the same, the charge is materially false as well. For Christ to be able to offer up the sacrifice that he did on our behalf, he had actively to resist the satanic powers and principalities arrayed against the kingdom of God. In other words, precisely through his obedience that qualified him to be our representative and substitute, he embodied the kingdom of God among us. His holy life was a perfect testimony to the perfect will for human flourishing according to God’s covenant standards. Advocates of penal substitution get to read all of the same gospel stories, teachings, commands, and so forth.

It must be remembered that PSA does not need to be separated off from other aspects or angles of the atonement such as his victory against the powers. As we said earlier, just because PSA is seen as the lynchpin securing the victory of Christ over the powers, that doesn’t mean that we have to sidelines the Gospels’ testimony about Christ’s cross-bearing life as an active resistance against the powers of oppression. That is a false dichotomy that needs to be forcefully rejected. Jeremy Treat’s newest book The Crucified King decisively answers it. Indeed, in this he is only following the tradition. Witness Calvin who seamlessly integrates both understandings:

Therefore, by his wrestling hand to hand with the devil’s power, with the dread of death, with the pains of hell, he was victorious and triumphed over them, that in death we may not now fear those things which our Prince has swallowed up [cf.1 Peter 3:22, Vg.]. –Institutes, II.16.11

Quotes like this could be piled up from Luther, Calvin, and countless other Protestant stalwarts.

Finally, the cross as judgment does not undermine the moral life for a number of reasons. First, we are provoked to a life of obedience in gratitude for God’s great forgiveness. Second, we only participate in the benefits of Christ’s cross-work only when we are united with Christ in the power of the sanctifying Spirit. The aim of PSA is the restored, regenerate disciple who is being increasingly conformed to the image of Christ.

7. Is the God of PSA a God who says “Do as I Say Not as I do?” Does he tell us to forgo vengeance and then go and exact it? Isn’t that inconsistent? Actually, no.God is God, and we are not. The Creator/creature distinction is the grounding of a lot of ethics in the Bible. God often says to us, “Do as I say, not as I do precisely because that is only mine to do.” In general, there are a number of things that are appropriate for God to do given his role as God, King, Judge, Creator of all the earth, that it is not permitted for us to do as humans, created things, sinners, and so forth. For instance, it is entirely appropriate for God to seek and receive worship. In virtue of his infinite perfections, his beauty, his glory, his majesty, his love, and goodness, God is absolutely worthy of worship and for him to demand or receive it is simply a right concern for truth. On the other hand, it is wicked for us to receive worship or to seek it. I am a created thing as well as a sinner, and therefore I am not worthy of worship.

Turning to the subject of judgment, punishment, and retribution we find Paul writing, “Repay no one evil for evil, but give thought to do what is honorable in the sight of all. If possible, so far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all. Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God, for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord’ “(Romans 12:17-19). In this particular passage Paul says not to inflict judgment on your enemies, not because God never does that sort of thing, but because he is said that’s the sort of thing only He should do. The explicit logic of the text is, “Don’t do that. It is my job. I do not want you taking vengeance. Vengeance is mine.” Paul was not squeamish about this sort of logic the way a number of anti-PSA advocates are because it’s all over the Old Testament. The Law (Exod. 20:5), the Psalms (Ps. 75:7), and the Prophets (Ezek. 5:8) tell us that God is the judge of the world and so it is his particular job to take care of things, vindicate whoever needs vindicating, rewarding those who should be rewarded, and punishing those who ought to be punished. He is the sovereign Lord of the world with the authority and might to execute judgments (Ps. 94). There is no thought that judgment or punishment is inherently wicked in the Hebrew Bible, especially in the hands of the righteous Lord of all the earth.

8. God tells us to just forgive, so why can’t he just forgive? Why does he need to punish us? Isn’t that the negation of forgiveness? Forgiveness at its most basic level is the generous release of an acknowledged debt. In commercial terms, which is where we derive the image in the NT, it is saying, “You owe me this, but I’m not going to make you repay.” Transferring it to the moral realm, “That was wrong, but I’m not going to make you suffer for it.” Instead of payment, though, condemnation of sin is at issue. For us to forgive someone is for us not to condemn them for an acknowledged wrong-doing. Taking into consideration God’s role in the universe, it is entirely reasonable to think that God’s forgiveness will look slightly different from ours. As we’ve already noted, God is King and Judge of the world. Part of his faithfulness to creation is to execute justice within it, to maintain the moral order he has established–which is not some impersonal justice, but one that is reflective of his own holy nature–in essence, to make sure that that wrongdoing is condemned and punished. Justice involves more than that, but certainly not less.

Given this, forgiveness cannot be a simple affair of “letting it go”, or passing it over for God. His own character, his holiness, his righteousness, his justice means that he cannot treat sin as if it did not happen. And it bears repeating that we don’t want him to. We honestly don’t want a God who looks at sin, idolatry, murder, oppression, racism, sexism, rape, genocide, theft, infidelity, child abuse, and the thousand dirty “little” sins we’d like to sweep under the rug, and just shrugs his shoulders and lets it go. That is a God who is lawless and untrustworthy. As a number of the Fathers said, a God who doesn’t enforce his law is a God whose word cannot be trusted.

All the same, the cross is the way that God makes that sin is punished and yet still forgives sinners by not making them suffer for sins themselves. PSA is not a denial that God forgives, but an explanation of how God forgives justly. It is how He, as King of the universe, goes about lovingly forgiving His enemies who deserve judgment. He suffers the judgment in himself. Once again, this whole explanation is articulated within a Trinitarian framework in which the Father, Son, and Spirit are all cooperating to achieve atonement. The Father is not pitted against the Son because the Father sends the Son in love and the Son, out of love, voluntarily comes in the Spirit to offer up his life in our place. The Son suffering judgment on the cross is God forgiving us.

The second thing to recognize is that our forgiveness is dependent upon his forgiveness, on the basis of Christ’s atoning work. We can let things go, forgive as we’ve been forgiven, forgo vengeance, and avoid retribution because we know that these things are safely in God’s loving hands. We do not have to exact judgment. Justice for the sins I suffer are handled the way my own sins are handled–either on the cross or at the final assize.

9. Some charge that PSA points us to a God who has to be convinced to love us. He can only love us after he gets rid of his wrath against us. Again, I am sorry if you’ve heard presentations like this, but against the classic accounts, the charge just misses the point. In PSA, the Father sends the Son precisely because he does love us. He sends the Son out of love to deal with the just judgment that hangs over us because of sin, to defeat the powers the stand against us, and to bring us back into relationship with himself, though justly. Calvin himself says quite clearly that God’s love is the deep motivation for Christ’s atonement:

Therefore, to take away all cause for enmity and to reconcile us utterly to himself, he wipes out all evil in us by the expiation set forth in the death of Christ; that we, who were previously unclean and impure, may show ourselves righteous and holy in his sight. Therefore, by his love God the Father goes before and anticipates our reconciliation in Christ. Indeed, “because he first loved us” [1 John 4:19], he afterward reconciles us to himself. But until Christ succors us by his death, the unrighteousness that deserves God’s indignation remains in us, and is accursed and condemned before him. Hence, we can be fully and firmly joined with God only when Christ joins us with him.

I could go on to find text after text and multiple analogies here. Say my friend wrongs me. I am angry with him because he stole from me and he has made himself my enemy. I might go pursue him out of love and friendship and yet still insist that there be an apology and acknowledgement of wrongdoing even while I look to forgive the debt.

I suppose it is appropriate here to clarify what is meant by wrath. God’s wrath is not some irrational flare-up of anger and foaming hatred. Wrath is God’s settled, just attitude of opposition towards all the defaces creation. It is his stance and judgment of displeasure towards sin, as well as his will to remove it. It also must be noted that God’s wrath needs to be qualified by the doctrine of impassibility and analogy. God moves to remove wrath, or his stance of opposition to our guilt and rebellion, precisely because he already loves us. It is quite possible for God to have complex attitudes towards his creatures.

For those still thinking of denying wrath, or aiming to pit wrath as antithetical to love, I’d suggest you consult Tony Lane’s excellent article on “The Wrath of God as an Aspect of the Love of God.” Indeed, for those who affirm it a little too violently, I’d suggest you read it as well as it corrects a number of unbiblical exaggerations and distortions preachers can fall into in their zeal to be “biblical.”

10. Related to this, it is claimed that PSA pits divine attributes against each other. Holiness v. mercy, love v. justice, and so forth, threatening the unity of God.While some popular presentations trend this way, as I mentioned before, classically the truth of God’s action on the cross has always been held consistently with the truth of God’s simplicity. It functions as a qualifier on every statement about God’s attributes and actions. So God’s holiness is not at variance with his mercy or his love with his justice. God is fully loving, just, righteous, and fully himself in all of his acts in history. And yet in the narrative of his historic dealings with Israel, it is not always easy to see the consistency and unity of his character. At times he judges immediately, and yet in others he shows mercy and delays wrath. He is named variously as Father, Judge, King, Lover, Friend, and the roles seem to come up in apparent conflict within the narrative of Scripture itself.

Properly conceived, though, PSA is about demonstrating the fundamental unity and consistency of God’s good character by resolving the narrative tension given in the Bible’s portrait of God. In that sense, God’s action on the cross is the revelation and enactment of his mercy, justice, love, holiness, wisdom, sovereignty, power, and grace, all simultaneously displayed. It is not about pitting his attributes against one another, but displaying their glorious, harmony as the culmination of his historical redemption. It is holiness as mercy, love through justice, and so forth.

11. It is often said that PSA as an account does not need Resurrection. It just stands alone, concerned only with Christ’s death for sin.Let me say that, yes, many popular accounts have been presented in this fashion. However, once again, this is not necessarily the case. If you look at the best exponents and defenders of penal representation as a strand of atonement, there is absolutely a place for Resurrection as part of God’s act in Christ. First, the resurrection is the public announcement that Jesus’ death for sin counts. Second, resurrection is itself the public vindication and justification of the Messiah and his people. As Paul says in Romans 4:25: “he was handed over for our sins, and raised for our justification.” According to N.T. Wright, Michael Bird, and a number of Reformed theologians, resurrection itself is the justifying act. The cross clears away our guilt, but it cannot stand alone.

Also, again, PSA is an angle on, but not the only truth of atonement. It deals with guilt, wrath, and the grip of death, but not death itself. Resurrection is still very much needed to accomplish Christ’s victory over all that stands against us. You can find this in Calvin, Bavinck, and many other stalwart defenders and exponents of penal substitution. There simply is no conflict and definitely a place for the resurrection in a system with penal atonement in it. On all of this, I would further suggest Michael Bird, Michael Horton, and Robert Letham as well.

12. Penal substitution is presented as an abstract legal transaction that sort of floats above history, concerned with a sort of celestial mathematics to be solved. It is a legalistic abstraction. While this might be true of Evangelical youth camps, it is definitely not of classic Reformed presentations. The “law” whose judgments must be satisfied is not some abstract idea floating around with other Platonic ideas in the realm of the forms. No, the idea of the law is grounded in the history of the covenants, which are inherently legal documents.

Adam broke the covenant in the Garden by explicitly violating God’s express command. That law is God’s revealed will in history. Law refers to God’s covenant charter with Israel expressed in the Sinai covenant, the book of the Law, and the Deuteronomic covenant. You can think of these laws as Suzerain-Vassal covenants where Israel’s love and loyalty are pledged, and blessings are given out with obedience, while curse/punishment is threatened for disobedience. Or again, it is like a marriage covenant, a set of promises with binding stipulations enforced by law. There is the promise of love, blessing, and joy with fidelity, but for infidelity/disobedience there lies the curse of divorce from the covenant God. The concept of law, blessing, and curse is present throughout the whole of Torah, the historical narratives, the Psalms, and the Prophets who act as God’s covenant enforcers. This is the background for Paul speaking of Christ suffering the curse of the law for us. It is within this framework in which Christ acts as the covenant representative. On all of this, I suggest consulting Michael Horton’s Lord and Servant.

We have, then, not some abstract legal theory foisted upon the text because Anselm could not think past his medieval, feudal context. Indeed, if anything, this was something that Anselm’s feudal context allowed him to pick up on better than our modern one can. No, in PSA we have careful reflection on the shape of the biblical narrative and an atonement derived from its own categories.

13. Another more political charge is that somehow PSA is tacitly supportive of the status quo and prevailing power structures of oppression. Honestly, I have a hard time taking this one as seriously as the others because the connections are so tenuous. It is usually caught up in the dubious narrative of the Constantinian fall of the Church, Anselm accommodation to the cozy church/state relationship, and other theological conspiracies. Still, say for the sake of the argument that PSA has been associated or used as a way of supporting power structures, I would argue that it is not inherently so. If it has, this is an abuse of the doctrine and the quirk of historical happenstance, not the necessary inner-logic of the position.

First, we must again note that PSA is not necessarily separate from Christus Victor themes. To the extent that it has, that has been a serious a doctrinal mistake. Through the cross Christ is reestablishing his rule against the powers, exposing their false claims, and releasing people from the fear of death. Beyond that, it’s been often pointed out by advocates of other theories that on the cross, God stands with the victims by identifying with them. I think there is a real truth there. Still, I would move on to say that the unique contribution of thinking of the cross as judgment is that it stands as a warning against oppressors. Yes, there is repentance available because Jesus has dealt with sin on the cross, but also note that God’s judgment is coming. Those are your options: repentance and forgiveness, or God’s just wrath against your consistent oppression of the weak, the poor, and the powerless. This seems to be is a powerful witness against oppressive power structures that deface and destroy all that God loves.

14. It could also be argued that PSA could be used as a supporter of inequality among the sexes or races. If guilt is simply atoned for, we can passively accept unjust social situations. If people have used PSA as an excuse to sit comfortably with abuse, this is a gross abuse and caricature. The cross as judgment for sin is the great leveller of human pride that declares all have fallen short of the glory of God, Greek and Jew, male and female, and all stand in need of grace, forgiveness, and the mercy offered. All have offended against God by violating his law and in violating each other, his Image-bearers in some way or another. And so all go to Christ together for mercy. Indeed, the cross is where these inequalities go to die. As the old phrase has it, “the ground is level at the foot of the cross.”

By placing the vertical claims of justice at the center of the cross, PSA does what Christus Victor and many of the other atonement angles can’t do: reconcile us to each other by dealing with the history of wrongs, sins, oppression, guilt, shame, and violence. In Christ, the dividing line is torn down through the blood of his cross and one new humanity is wrought in him, the Church (Col 1:15-20; Eph. 2:10-20). For a beautiful exposition of the way Jesus’ cross-work brings about reconciliation and repentance, see Trillia Newbell’s little book United: Captured by God’s Vision for Diversity.

15. Many charge that PSA is legalistic due to its narrow focus on law, punishment, and so forth. While we’ve already dealt with this to some degree, the Bible does say that while it is more than this, sin is at least law-breaking (1 John 3:4). The legal dimension of sin is real and needs to be dealt with definitively. In that sense, PSA is as legalistic as the Bible is. Now, it is true that insofar as PSA has been divorced from other angles on the cross it becomes narrowly legalistic, sure. But as we’ve seen over and again, that need not be the case.

16. Many claim that PSA encourages violence. Divine violence against sin is imitated by humans on earth, unleashing violence against one another.First of all, this objection usually assumes a theological pacifism based on quite contestable interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount (and even then, usually only a few verses within it). Then, this pacifistic hermeneutic is extrapolated and superimposed upon the entire Scriptures. Often it is connected with some Girardianism that sees “violence” as the aboriginal heart of sin to be avoided in all instances. Despite the copious amounts of biblical evidence that God uses force or “violence” in his judgments, an idiosyncratic, non-violent Jesus is held up as counterpoint that rules all of that out. Indeed, in many cases this hermeneutic is used to simply eliminate texts from the canon, or create an overriding canon within the canon that simply rules out key verses on atonement.

But for those intending to be faithful to Scripture, it is simply a matter of the biblical record that God is not personally a pacifist. Hans Boersma has argued that God’s hospitality requires him to employ coercive force and violence. God hates human violence, but in a violent world, at times God deals in the violent exigencies of history. God judges the unrepentantly violent by handing them over to their own chosen means of living and dying. God is not violent in his being, but in order to hold back the tide of chaos and rage that threatens to destroy creation, he says, “this far you may come and go no farther”; and he backs it up.

Beyond that, this objection, again, assumes that all divine action in Scripture must be imitated. But this is simply not the case. In fact, there is plenty of space for those wanting to maintain a generally pacifist stance to see God’s judgment in Christ as his exclusive prerogative. In fact, Miroslav Volf has argued that the soundest basis for rejecting violence as a path for dealing with conflict at the human level is if we reserve it for the just, perfect judgment of God:

One could object that it is not worthy of God to wield the sword. Is God not love, long-suffering and all-powerful love? A counter-question could go something like this: Is it not a bit too arrogant to presume that our contemporary sensibilities about what is compatible with God’s love are so much healthier than those of the people of God throughout the whole history of Judaism and Christianity? Recalling my arguments about the self-immunization of the evildoers, one could further argue that in a world of violence it would not be worthy of God not to wield the sword; if God were not angry at injustice and deception and did not make the final end to violence God would not be worthy of our worship. Here, however, I am less interested in arguing that God’s violence is not unworthy of God than in showing that it is beneficial to us. Atlan has rightly drawn our attention to the fact that in a world of violence we are faced with an inescapable alternative: either God’s violence or human violence. Most people who insist on God’s “nonviolence” cannot resist using violence themselves (or tacitly sanctioning its use by others). They deem the talk of God’s judgment irreverent, but think nothing of entrusting judgment into human hands, persuaded presumably that this is less dangerous and more humane than to believe in a God who judges! That we should bring “down the powerful from their thrones” (Luke 1:51-52) seems responsible; that God should do the same, as the song of that revolutionary Virgin explicitly states, seems crude. And so violence thrives, secretly nourished by belief in a God who refuses to wield the sword.

My thesis that the practice of nonviolence requires a belief in divine vengeance will be unpopular with many Christians, especially theologians in the West. To the person who is inclined to dismiss it, I suggest imagining that you are delivering a lecture in a war zone (which is where a paper that underlies this chapter was originally delivered). Among your listeners are people whose cities and villages have been first plundered, then burned and leveled to the ground, whose daughters and sisters have been raped, whose fathers and brothers have had their throats slit. The topic of the lecture: a Christian attitude toward violence. The thesis: we should not retaliate since God is perfect noncoercive love. Soon you would discover that it takes the quiet of a suburban home for the birth of the thesis that human nonviolence corresponds to God’s refusal to judge. In a scorched land, soaked in the blood of the innocent, it will invariably die. And as one watches it die, one will do well to reflect about many other pleasant captivities of the liberal mind.

–Exclusion and Embrace, pgs. 303-304

So then, even for those who accept a pacifist reading of the Sermon on the Mount, it’s not clear at all that one must embrace contemporary non-violent atonement theories.

17. A fairly important charge that is often made is that PSA is simply not found in the Fathers. It is a theological novelty that ought to be at least suspect.There are two responses to be made here. First, I am a Protestant and so while I hold a significant place for the witness of the tradition and the theological interpretation of the Fathers, what matters most is whether the doctrine is found in Scripture. As I indicated earlier, I think a very strong exegetical case can be made that it is indeed in the Bible and that has been amply demonstrated.

All the same, a number of scholars have been doing more research in the Fathers and indicating that while penal motifs are not the dominant picture of salvation in the Fathers, it’s definitely an exaggeration to say it is entirely missing. Indeed, there is good evidence that Fathers like Irenaeus, Athanasius, Chrysostom, Hilary of Poitier, Augustine, and a number of other Fathers included considerations of Jesus’ death as penalty and curse born on behalf of sinners. Consult the link for extensive quotations.

18. Some have charged that PSA is an inherently individualistic theology of sin and salvation linked to Western, modern categories of jurisprudence. It should be clear from what was said above about Jesus as our Messianic representative that this is simply not the case when it comes to a more classic Reformed account of things. The whole logic runs against individualistic notions of sin and punishment. Now, it is true that it has often been presented individualistically in our modern context. But that is nowhere inherentto the theology. Instead, penal substitution is the work of our covenant head Jesus, who takes responsibility for the sins of his people, the Church. My sin and guilt are dealt with as I am united to Christ and brought into the broader family of his forgiven, set-apart people. For more on this and the similar charge made against Anselm, see here.

19. PSA as a theory is fairly divorced from the narrative of the gospels, floating above them, like oil on water.While many have constructed the doctrine on the basis of Pauline proof-texts, I cannot see this charge holding water. I myself wrote four papers in seminary demonstrating penal dimensions to each of the Gospel-writers thought about the cross. Consulting N.T. Wright or Jeremy Treat’s work, or any number of other scholars doing biblical theology will reveal the way penal representation fits squarely within the mission and message of Jesus. I can’t to the exegetical work here, but roughly, Jesus came to restore the kingdom of God, fight the great battle against God’s enemies, and bring about the end of Exile of judgment for Israel. Jesus does this in accordance with Isaiah’s picture of the Suffering Servant, David’s Seed and true heir, who brings about a New Exodus by suffering a representative Exile for Israel on the Cross. This is how the great forgiveness of sins is brought about and the basis on which people are invited into the new Israel of God that’s been reconstituted in the person of Jesus. Again, roughly. For those who know the biblical themes, it all starts fitting together quite nicely.

I don’t have the time or the space, but we could talk about the Temple theology here, or Jesus the Lamb who takes away the sin of the world, or Jesus the innocent sufferer, or the ransom-sayings, or A.T. Lincoln’s work on the trial motif in John, and a half-dozen other sub-themes that connect Jesus’ mission in the Gospels to the penal dimension of his work. Indeed, N.T. Wright has said that his own work in Jesus and the Victory of God as the most extensive modern defense of penal substitution grounded in Jesus’ own self-understanding. Penal substitution isn’t an extraneous, foreign element needing to be grafted onto the Gospels, but an idea that sits quite comfortably at their heart.

Conclusions and Resources

While this has been absurdly long for a blog post, I’m well aware that this is ultimately inadequate. I am sure there are a number of questions I’ve left unaddressed, or addressed too quickly to be satisfactory for some. Still, I think it is been demonstrated that a number of the largest objections rest on misunderstandings, or mischaracterizations of the doctrine. What’s more, though I did not address every variation and objection out there, I think the seeds and forms of basic answers to those challenges are present in the various responses given. Many of the new objections are simply variations on older themes.

As I said before, though it is not the only work Christ does on the cross, his sin-bearing representation is at the heart of the gospel. While we need to be careful about using it as a political tool to establish Christian orthodoxy, the issues at stake make it worth defending with grace and care. The justification of God’s righteousness in the face of evil, the graciousness of grace, the finality and assurance of forgiveness, the costliness of God’s love, and the mercy of God’s kingdom are all caught up in properly understanding the cross of Christ.

Soli Deo Gloria

For those looking for more concrete resources, I would point you to these excellent works.

Articles

Books

These are generally holistic accounts that do an excellent job with the biblical material:

- The Cross of Christ by John Stott. The classic Evangelical standard.

- God the Peacemaker by Graham Cole. A newer, all-around balanced account.

- The Crucified King by Jeremy Treat. New favorite on reconciling PSA and CV, and setting them both in biblical-theology categories

- The Apostolic Preaching of the Cross by Leon Morris. Older, but still solid exegetical and linguistic work.

- Mysterium Paschale by H.U. Von Balthasar. Though this only has 30 pages on Good Friday, they’re absolute gold. I cannot overstate how good that chunk is.

- The Glory of the Atonement. An excellent collection of biblical, historical, and theological articles on atonement. Vanhoozer’s essay on atonement in postmodernity alone is worth the price.

For those interested in postmodern critiques from violence, Girardianism, feminism, postcolonialism, and so forth, I highly commend these works:

- Violence, Hospitality, and the Cross by Hans Boersma. Particularly good on violence, Girardianism, etc.

- King, Priest, and Prophet by Robert Sherman. Another balanced, explicitly Trinitarian account attuned to postmodern criticisms.

- Atonement, Law, and Justice by Adonis Vidu. I’ve only skimmed this, having just received it, but it very well might be among the most important books on atonement to come out in the past 10 years.

(Finally, I must say thanks to Alastair Roberts and Andrew Fulford for looking at earlier drafts. Their advice made this much better than it was. Any failures that remain are mine.)

If you follow any discussions about the Trinity nowadays, you’re likely to hear the idea of “perichoresis”, or the mutual indwelling of the Father, Son, and Spirit. It’s long been a piece of trinitarian theology. But does it and should it have applications elsewhere in our theology? Like our doctrine of humanity, or our view of creation? That’s the issue we take up this week on Mere Fidelity as we interact with this article by Peter Leithart.

If you follow any discussions about the Trinity nowadays, you’re likely to hear the idea of “perichoresis”, or the mutual indwelling of the Father, Son, and Spirit. It’s long been a piece of trinitarian theology. But does it and should it have applications elsewhere in our theology? Like our doctrine of humanity, or our view of creation? That’s the issue we take up this week on Mere Fidelity as we interact with this article by Peter Leithart.