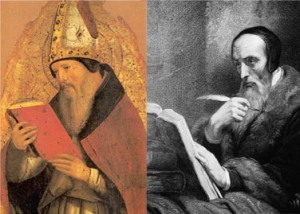

It doesn’t take a specialist to know that Calvin loved the writings of St. Augustine of Hippo. After the Bible, he quotes Augustine more than anybody else in the Institutes (I think, but don’t quote me on this) more than all the other Fathers combined. Whenever he wanted to establish the antiquity of a doctrine, or its soundness with the interpretation of the Church universal, it’s a safe bet he’s going to pull out an Augustine quote, especially since he was an authority both he and his Roman interlocutors agreed upon.

It doesn’t take a specialist to know that Calvin loved the writings of St. Augustine of Hippo. After the Bible, he quotes Augustine more than anybody else in the Institutes (I think, but don’t quote me on this) more than all the other Fathers combined. Whenever he wanted to establish the antiquity of a doctrine, or its soundness with the interpretation of the Church universal, it’s a safe bet he’s going to pull out an Augustine quote, especially since he was an authority both he and his Roman interlocutors agreed upon.

Calvin’s Quibbles

That said, Calvin wasn’t a slavish admirer of the great bishop as we see here in his comments on the story of Pentecost:

And when. To be fulfilled is taken in this place for to come. For Luke beareth record again of their perseverance, when he saith that they stood all in one place until the time which was set them. Hereunto serveth the adverb, with one accord Furthermore, we have before declared why the Lord did defer the sending of his Spirit a whole month and a half. But the question is, why he sent him upon that day chiefly. I will not refute that high and subtle interpretation of Augustine, that like as the law was given to the old people fifty days after Easter, being written in tables of stone by the hand of God, so the Spirit, whose office it is to write the same in our hearts, did fulfill that which was figured in the giving of the law as many days after the resurrection of Christ, who is the true Passover. Notwithstanding, whereas he urgeth this his subtle interpretation as necessary, in his book of Questions upon Exodus, and in his Second Epistle unto Januarius, I would wish him to be more sober and modest therein. Notwithstanding, let him keep his own interpretation to himself. In the mean season, I will embrace that which is more sound.

While according him great respect and noting his interpretation, Calvin says that the great Augustine has put forward what he considers to be a less “sober” and “modest” interpretation which he simply cannot follow. So what explanation does he find more plausible?:

Upon the feast day, wherein a great multitude was wont to resort to Jerusalem, was this miracle wrought, that it might be more famous. And truly by means hereof was it spread abroad, even unto the uttermost parts and borders of the earth. For the same purpose did Christ oftentimes go up to Jerusalem upon the holy days, (John 2, 5, 7, 10, 12,) to the end those miracles which he wrought might be known to many, and that in the greater assembly of people there might be the greater fruit of his doctrine. For so will Luke afterward declare, that Paul made haste that he might come to Jerusalem before the day of Pentecost, not for any religion’s sake, but because of the greater assembly, that he might profit the more, (Acts 20:16.) Therefore, in making choice of the day, the profit of the miracle was respected: First, that it might be the more extolled at Jerusalem, because the Jews were then more bent to consider the works of God; and, secondly, that it might be bruited abroad, even in far countries. They called it the fiftieth day, beginning to reckon at the first-fruits.

-Ibid

We see here the difference I’ve mentioned before when it comes to the Reformers and the earlier, especially medieval, hermeneutical tradition; they will usually privilege the ‘literal’/historical-grammatical sense of the text over any spiritualizing, allegorizing, or typological senses. Calvin isn’t opposed to typological interpretation in principle–he engages in quite a bit of it himself and accepts the prefigurement of Pentecost in the sense of first-fruits pointing towards the initial fruitfulness of the Gospel by the Spirit’s power. He’s concerned, though, that the interpretation first be grounded plausibly in the history of the event. In other words, in a text like this, he insists that the intentionality of the human actors be made sense of and that “the profit of the miracle was respected.” Only then may we move on to the typological meaning without it becoming over-subtle.

Now, that said, I myself think Calvin was being a little over-cautious here; Augustine’s got a point linking Pentecost with the giving of the Law, and the Spirit who writes the Law on our very hearts. Part of the point of typology is that God’s authorship of history can transcend even the human actor’s, or author’s original intent, without violating them. Also, given modern studies in the theological dimension to the authorship of the Gospel writers, it doesn’t strike me as improbable that Luke intended for multiple resonances to be in play in the text connected to as rich a concept as Pentecost.

The Moral of the Story

More interesting than the specific interpretation given to the passage however, was Calvin’s treatment Augustine’s interpretation. Here he offers us a model for a Protestant engagement with the interpretive tradition of the Fathers: respectful, but critical listening. He doesn’t do what so many pop-Protestant approaches do and simply ignore the tradition because, “All I need is my Bible.” Calvin knows that the Church, at least some segments of it, has been reading the Bible well enough for a very long time, so he doesn’t need to reinvent the wheel. He knows the arrogance it takes to approach the text in a way that says the Spirit has skipped 20 centuries of interpreters in order to finally reveals the Scriptures to me. In fact, it is precisely through the teachers of the Church that he works most of the time.

At the same time, in order that the Spirit may truly rule through the Word, Calvin reads the Fathers critically–not disrespectfully, but with a knowledge that they are fallible men, who can err just as he might. As you would treat a respected pastor who has faithfully labored over the texts for years, so with the Fathers: pay careful attention to what they have to say, consider deeply, and go back to the text. Indeed, this lesson is valuable, not only for Protestants looking to read the Fathers, but for Protestants looking to read the early Reformers; Calvin teaches me by his disagreement with Augustine that it’s permissible for me to disagree with Calvin!

Soli Deo Gloria