A little less than 100 years after Christ triumphed over the old Roman gods, the Goths under the Arian-Christian King Alaric followed suit and sacked Rome–mostly just to show they could. The physical impact was relatively minimal but, as historians are quick to point out, the political and psychological impact was cataclysmic. Among varied responses to the sack were those of the pagans who laid Rome’s historic defeat at the feet of the Christians and their new God. By abandoning the sacrifices of the old gods, they had provoked them, lost their protection, and had been left defenseless against the assault.

A little less than 100 years after Christ triumphed over the old Roman gods, the Goths under the Arian-Christian King Alaric followed suit and sacked Rome–mostly just to show they could. The physical impact was relatively minimal but, as historians are quick to point out, the political and psychological impact was cataclysmic. Among varied responses to the sack were those of the pagans who laid Rome’s historic defeat at the feet of the Christians and their new God. By abandoning the sacrifices of the old gods, they had provoked them, lost their protection, and had been left defenseless against the assault.

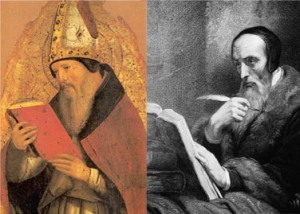

It was in response to this reality that Augustine of Hippo penned one of his crowning theological achievements: The City of God. His basic point was to answer the charges of the pagans, but in the process he lays out a broad vision of God, his purposes in history, politics, philosophy, and dozens (if not hundreds) of other issues.

To my shame, I must say that despite good intentions for many years, I have only just begun to read it this week. Thankfully, it’s already repaying the time invested with insights relevant to the present moment. One passage in particular in Chapter 35 of Book 1 is worth meditating on for a bit:

But let this city bear in mind, that among her enemies lie hidden those who are destined to be fellow citizens, that she may not think it a fruitless labor to bear what they inflict as enemies until they become confessors of the faith. So, too, as long as she is a stranger in the world, the city of God has in her communion, and bound to her by the sacraments, some who shall not eternally dwell in the lot of the saints. Of these, some are not now recognized; others declare themselves, and do not hesitate to make common cause with our enemies in murmuring against God, whose sacramental badge they wear. These men you may today see thronging the churches with us, tomorrow crowding the theatres with the godless. But we have the less reason to despair of the reclamation even of such persons, if among our most declared enemies there are now some, unknown to themselves, who are predestined to become our friends. In truth, these two cities are entangled together in this world, and intermixed until the last judgment effects their separation.

The line that really grabbed me was that bit about “among our most declared enemies there are now some, unknown to themselves, who are predestined to become our friends.” According to Augustine, there are Two Cities in the world, the City of God and the City of Man, and until the future judgment their citizenry are mixed up and jumbled together–hidden, as it were, in plain sight.

History is not immediately transparent before our eyes. Eschatological judgment and the course of history under the guidance of God’s providence will contain surprises that unsettle our too-confident sense that we have a read on things as they are. From this truth, Augustine deduces that Christians are not to despair in the face of even the most virulent opposition.

Why? Because in the sovereign grace of God, it may be that our bitterest enemies may end up our staunchest friends. It is very easy when looking out at the headlines today to embrace a narrative of decline–which may be more or less correct–and then conclude we must settle for a defeatist attitude, bunker up in our churches, and wait out the storm. Or, more personally, it’s possible to look out at our Facebook feeds, Twitter threads, and look at some whom we see to be most hostile, vocal, and critical towards Christian faith and its moral vision, and simply write people off. In our arrogance and finitude, we freeze them as they are, passing judgment before the time (1 Cor. 4),

Augustine has a far different view. God is not bound by the exigencies of history. Trajectories exist, it is true, but God is the God who is Lord over history, both cosmic and personal. What’s more, he is the God of mysterious grace. This is why Augustine can urge hope for our “enemies”–the grace of God overcomes the opposition of those who hate him, through the good news of the gospel. Augustine knew this personally because of his own story of conversion from scoffer to Bishop. But also because of the Apostle whose letters exerted such a magnificent influence on his own theology: Paul, the chief persecutor of the Church whom God called to be her greatest missionary and theologian.

In other words, it is a betrayal of the gospel to lose hope for our enemies, our communities, or even a culture that seems dead-set to gut whatever is left of its philosophical underpinnings inherited from the gospel.

Of course, it wouldn’t be Augustine if he didn’t also highlight the inverse truth: some of our current friends may turn out to be ultimately false believers who end up abandoning and betraying the gospel. We can all think of any number of friends or pastors who seemed to start out so strong, but before the end, turn away and–even worse–drag a number with them. This is the Augustinian limit and caution on hope: set it on the right object.

Our hope for the world, for our neighbor, even our enemies, is ultimately not in human teachers, political programs, or the right method of “engagement.” Our hope is in the God who speaks the world out of nothing, light out of darkness, and a word of justification in the midst of the most damnable moment in history–the cross of his own Son.

We have reason for hope–his name is Jesus.

Soli Deo Gloria