After a number of months of having it on my to-do list, I finally got around to reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me. Written as an extended letter to his teenage son, Samori, it is part memoir, part manifesto, and part social history, giving voice to Coates’ experience growing up Black in America—with all the ironies, tragedies, dangers, and, yes, joys that affords.

After a number of months of having it on my to-do list, I finally got around to reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me. Written as an extended letter to his teenage son, Samori, it is part memoir, part manifesto, and part social history, giving voice to Coates’ experience growing up Black in America—with all the ironies, tragedies, dangers, and, yes, joys that affords.

I guess I read it for some familiar reasons. Like many, I’ve read Coates’ thoughtful and provocative pieces on race, justice, and public policy at The Atlantic. My curiosity was provoked by the wide variety of conflicting reviews of it, ranging from fawning praise to cynical rejection.

I’d like to say the biggest reason I read it was to try to and better understand my friends, my brothers and sisters in Christ, my fellow Image-bearers, who live, day to day, in a different set of skin than I have. At least, as much as reading a book can help with that. If I’m honest, I think it’s important to kids like me (having grown up in schools reading about the Civil Rights era) to remain aware of the conflicted reality of race in America. And I say this as someone not typically prone to liberal, white guilt, since I’m not liberal (being raised conservative), nor white (being Arab/Palestinian and Hispanic, a first-generation, somewhat Brown man born in the States).

The experience—because it’s something of an experience reading Coates—was challenging, nonetheless, both emotionally and intellectually. As a theology student, it’s become impossible to avoid reading texts like this in theological perspective and processing them in that fashion. But I don’t think I have to stretch things too much to see the work as a deeply theological one. Indeed, despite his avowed atheism, I found much of Coates’ analysis down-right Pauline.

In what follows, I’d simply like to note some the broadly theological points of contact with and criticism of Coates work and the Christian gospel. None of what I say will be ground-breaking or likely that eye-opening. All the same, I do feel the need to process this as best I know how, so here goes.

The Body

My first impression was related to the feature of the work that almost every commentator I’ve read has touched on: the viscerality and physicality of its anthropology. Coates’ writes constantly of the experience, the value, the suffering, the reality of living in the black body. Philosophically this flows in part from Coates’ materialism, but there’s more to it than that.

With story, with carefully chosen metaphor, and torrentially applied adjectives and verbs, Coates aims to communicate the experience, the consciousness of living as a black body who can be taken, dominated, used, threatened, destroyed, and plundered at all times with seeming impunity. The hardness, the constant fear, then, of growing up on the streets of Baltimore, is not merely psychological, but physiological, welling up in your bones, your muscles, tendons, and instincts too close, too raw, too ingrained by force of history, experience, and even birth to be a strictly philosophical reality.

In attempting to understand, we instinctively reach for analogous situations, even if they don’t quite fit. The closest I’ve come is thinking about life in post-9/11 as an Arab in the States with the last name Rishmawy. I remember getting called sand-nigger, dune-coon, and Taliban on the football field where I got speared in the back for being a “Palestinian.” I remember the chilly sweat that broke out on my skin at the airport, when the guard at the metal detector told me I’d “be in a world of hurt” if the detector went off again when I walked through. As I thought about rendition stories I’d read about, it didn’t matter that I had my cross necklace and Bible in my backpack and coming home from a mission trip—the threat to my young, Arab body coursed in every nerve of my soul. It was a reality bodily and yet more than simply bodily. But again, it’s only an analogy.

In any case, throughout the whole work, every time he spoke of bodies I kept thinking through the dynamic of flesh/body (or sarx/soma) in the New Testament. At times, these terms can simply refer to the physical, biological material of the person—flesh and bones. But most biblical scholars will point out that more often than not, these terms are more of a complex of the spiritual and historical forces that are located within our lived, physical reality. In Paul, the sarx can refer the corpse as the site of the created and fallen dimensions of human experience and nature apart from Christ, while the body is often referring to embodied, human experience in the renewed sphere of the Spirit in Christ.

As I noted, Coates’ viscerality is quite materialist—his description of the spirit and the soul as the charge flowing through his nerves is formally reductionistic in that the physics of the body are all there is. But in another way, his emphasis is quite biblical, even Pauline. Christians confess in their creed, not merely the immortality of the soul (though we affirm it), but the resurrection of the body in its fully physical, material, social, and historical dimensions. To certain forms of spirituality and philosophy, Christianity’s focus on resurrection can appear crassly materialistic. But for Paul, what we do in the body, not merely in our “spirits”, matters. We were created and redeemed, body and soul, at a price–so the body is an object of moral concern and a site of moral care (1 Cor. 6:12-20).

Many of us can tend to lose sight of that, however, losing our understanding of the damning, bone-crushing, destructive, disembodying (quite literally) nature of sin, or the gloriously physical relief that the resurrection promises. Coates’ language, his emphasis, I think, has the salutary effect of reminding some of us Christians of the material dimensions of being created good as bodies in the world. As Christians, we surely believe there is more, but we must not believe there is any less.

Sin and “The Dream” as Kosmos

Coates is also a theologian of sin. This is almost more obvious than the viscerality of his language. For Coates, to tell the story, the history, the experience of the black body is to tell the story of its plundering, its rape, enslavement, subjugation, and burial under the edifice of white society and persons who “think themselves white.” Narrating the black body means narrating the sins committed against it.

There isn’t a blind, Manicheanism in Coates’ telling, though, with pure martyrs and pure villains. I was struck throughout the whole at Coates’ self-analysis, his coming to self-consciousness and questioning of his own motives, his own narratives, his own ideas that he speaks of in response to his mother’s writing assignments. Coates operates with a heavy hermeneutic of suspicion, but one that’s aware of the pervasive nature of sin in the self–in all selves—especially his own. It’s downright Puritanical (not in the bad sense) in terms of its self-interrogation.

Connected to this theology of individual sin is his broader cosmology and theology of culture as expressed in his idea of “The Dream”, which he outlines for his son and constantly warns him against. For those acquainted with biblical cosmology, the Dream functions like “the World” or kosmos in John and Paul. The world is not simply the physical creation, but rather the cosmos including and especially human culture under the power of sin, hostile to God and his ways of peace. For the Christian, the world with its desires, pressures, systemic drives, and allure to conformity threaten to overwhelm the believer with its ways of thinking, behaving, and being. It presents us with visions of the good life (money, sex, power, success, etc) and the standard, often-times godless patterns of procuring it.

The Dream, for Coates, is that of living “white”, of acting white, sequestered away in the safe, suburban communities, built on the sweat, tears, blood, bones, and centuries of black bodies plundered for their wealth–separated from the hard streets of Baltimore where being black and a child could still get you robbed of your body. It is a dream upheld and made manifest in school systems, social practices ranging from slavery to redlining to arrest quotas to the common trope that because a young, black man won’t keep his pants up and shows the defiance to authority common to most 15-year old boys, he’s kind of asking to get shot. Indeed, when you look at it closely, it’s not just that the Dream functions as the World, in many ways it serves as an angled description of what Scripture is actually speaking to.

And so, every time Coates tells his son Samori to resist the deep-seated ways his culture will try to shape and form his affections, his assumptions, his own dreams, desires, and prejudices, I just keep hearing Paul say, “Do not be conformed to the patterns of this world…” (Rom. 12:1-2).

This, I think, is connected to that deep sense of sin as act and Sin as Power. That’s not how he’d put it, of course, but there is a very thick theology of universal, personal complicity, and at the same time of an external, systemic, supra-personal Power that enslaves, enlists, and overwhelms. It’s not just whites, but blacks striving to be white, who are co-opted and conformed to the Dream. Again, it’s sin as individual acts, but more than that, it is Sin as a power that works its way into corporate systems that have their own logic that, in some sense, can’t be overturned simply by the exercise of the will of one, good-hearted individual.

As a Christian, I’m tempted to have recourse to the language of the demonic. Christians have always known that despite God’s rule and Christ’s reign, there is some sense in which world is “under the control of the evil one” (1 John 5:19), the god of this age who tends to blind and deceive the world about the truth, especially of the gospel (2 Cor. 4:4). Why wouldn’t he work through social and political systems to lie and wreak death in the world now, if that’s what he’s been doing since the beginning (John 8:44)?

Religion, Truth, and the Crucifixion of the Body

Naturally, following a discussion of the “plight”, a theological read of the book might lend itself to a section on “The Gospel according to Ta-Nehisi Coates.” But, to be honest, I couldn’t find one. I don’t believe that’s the point, either. Coates isn’t offering his son a grand, universal hope, a solution. He’s trying to prepare him for reality in a world without a coming universal redemption, with people and systems that don’t know they need one. To carve out a life—one with love, tenderness, integrity, and a sense of honest pride—neither enslaved, nor blind to the world as it is. As one friend put it—he’s preparing him for life in this present, evil age when that’s the only one on the horizon.

And this is where I think about Coates’ atheism and honest confession that he’s always been alienated from the comforts of religion, having never been raised with them. There’s an understandable ambivalence (though, I don’t sense a hostility) towards religious faith in the book. On the one hand, there is his early incomprehension at those taken with its comforts—their willingness to endanger their sacred, fragile, and single-shot bodies against clubs, against dogs, against death. Religion seemed to cultivate a carelessness about the body. “Do not be afraid of those who can kill the body…”

What’s more, there’s the problem of what Bonhoeffer called “cheap grace.” Coates has seen the quick rush to forgive in some churches and communities—calls that seem to glide quickly past the problem of Abel’s blood still wet on the pavement crying out for justice. Or the calls for non-violent suffering for black people from those watching the protests in the streets of Fergusson comfortably seated on their couches in the suburbs. Or reconciliation without any sense of restitution—or even an indictment. You can sense his realism, his history, his cosmic sense of injustice rise up much like protest atheism chronicled in Camus’s The Rebel.

How can religion of this sort not seem like a palliative?

All the same, Coates wonders if there’s something he’s missing out on. Something that he is alienated from in the faces and the souls of men and women he respects who believe differently on this score.

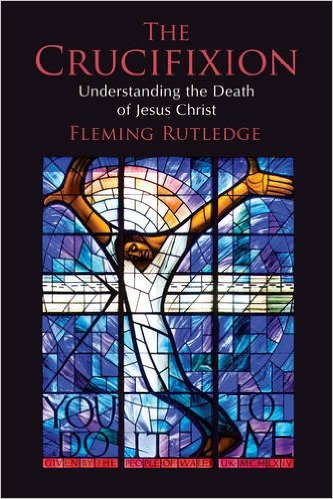

And this is where I think about the book I’m reading for Lent, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ by Fleming Rutledge. The front-cover is an image of the “Wales Window” given to the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. It was donated as a gift from the people of Wales after the 1963 Klan bombing that rocked the church and robbed the life of the four little, black girls in their Sunday best.

And this is where I think about the book I’m reading for Lent, The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ by Fleming Rutledge. The front-cover is an image of the “Wales Window” given to the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. It was donated as a gift from the people of Wales after the 1963 Klan bombing that rocked the church and robbed the life of the four little, black girls in their Sunday best.

The stained glass is striking. In it, we see a Christ with brown skin, arms outstretched. Rutledge notes that the position of his head hangs at the same angle as that of an ikon called “Extreme Humiliation.” According to the artist, the two arms outstretched are doing different things. The one is thrust out, stiff-arming the powers of death and injustice, while the other reaches out, offering forgiveness for the world. Under him are the words “You do this to Me”, which come from the parable of the Sheep and the Goats in Matthew 25. Here Christ identifies himself with his people, declaring that whatever is done or not done unto them, for good or ill, for woe or weal, for blessing or curse, “you do this to me.” You do this unto me.

The central mystery of the Christian gospel is the Holy God who out of the fullness of his own, perfect life stooped, became incarnate, identifying himself with the whole of humanity, and, as the Creed has it, suffered under Pontius Pilate. The Savior is the Divine Son who knew no suffering, yet assumed human flesh, a Body in midst of a dominated people to suffer on our behalf and rise again. God became a gendered, embodied Jew in the 1st Century, heir to hundreds of years of political oppression at the hands of colonizing invaders (Babylonian, Persian, Greek), mostly recently of an empire, Rome, that stood as the chief political, economic, social, and religious power the world had ever seen. He grew up under the eye of the soldiers of a people who prided themselves as superior to every other people; a people who used subject nations and cultures to prop up their own; a people who threatened anyone who crossed that system with torture and death. And eventually it was under the administration of their laws, their justice, that his body hung naked, exposed, broken, shamed on a cross, tossed on the garbage heap of history, scorned even by the elite of his own people. In the particular sense that Coates speaks of being black, or at least, not white—that is the space that the Son of God entered in his body. That is the place that his body died.

I cannot do justice to the multifaceted character of Christ’s death, not with 3,000, nor 3,000,000 words, but the thing we must say is that the death he died, he died willingly for sin. He died in order to wipe us clean from the sins we commit as well as deliver us from the Sin we are enslaved to. He died in order to atone and liberate. He died to do justice, to ensure that forgiveness is not offered on the cheap. That reconciliation does not simply walk past restitution and truth, or support a culture of impunity.

Indeed, one the most powerful accomplishments of Christ in the visceral, flesh-ripping, godlessness of the cross is the way it tells the truth and opens our eyes to the violence of sin in the world. The hideousness of the cross, Rutledge notes, the crucifixion of this man who is God, puts to flight sentimental religion and forces us to face up to the malignant, persistent ugliness of sin. It unveils reality, much as Richard Wright writes in the poem from which Coates draws his title. To look upon “the sooty details of the scene” of our Savior upon the cross is to have them “thrust themselves between the world and me.”

And I think this moment in the Gospel is important for me to sit with when reading Coates. Obviously, a concern for the body and Coates’ totalizing fear of its loss, of his ultimate powerlessness and inability to secure it or that of his son, is crying for an answer in the good news of the Resurrection. For Christians, death is not the concluding word, and in his resurrection, Jesus actively and powerfully breaks the power of Sin, the World, the Dream, by showing that despite appearances to the contrary, it does not have the final say of things. This is what gives us hope, gives courage, gives the moral steel that accounts for the paradoxical attitude of Christians towards the body: it is precious, it is good, it is inviolable, and yet it’s loss is not our absolute terror. God’s promises do hold us up.

But the resurrection only comes as good news after we’ve sat in the shadow of the cross. Jesus is the Resurrected one only as the Crucified one. Hope for reconciliation, both personal and cultural, only comes after we’ve truly reckoned with the nature of the rupture, confessed, and repented. This is one of what I take to be the glories of the Christian gospel: it forces you to see the truth about the world, about yourself, about your neighbor—both the grime and the glory—and it is precisely there where the God with a broken body meets us.

In Lieu of a Conclusion

I have no conclusion, really. With a book like Coates’ there’s always more to say. I haven’t weighed in specifically on any particular charges, critiques, details of history, or political implications to be drawn with respect to things like reparations or #BlackLivesMatter. And I’m not really sure that’s the point.

I suppose at the end of Coates’ work–beyond a better, heavier understanding of the struggles of my neighbors–I can’t help but come away with a stronger desire to plumb the depth of the Christian gospel, to grasp the power of Christ and him crucified and speak it into the darkest reaches of the human condition without maudlin or mawkish sentimentality. A hope hell-bent on truth. A reconciliation forged through justice. A God who enters our life and then invites us into his, saying, “This is my body, broken for you.”

Soli Deo Gloria

This week on Mere Fidelity, Alastair, Matt, and I tackle the subject of the Lord’s Supper. We try to set it in the context of the last week of Jesus, while moving around to the various Gospels and the canon of Scripture as a whole. This one–I think–had some particularly appropriate insights as we enter Holy Week heading towards Maundy Thursday and Good Friday. We hope you are as edified as we were.

This week on Mere Fidelity, Alastair, Matt, and I tackle the subject of the Lord’s Supper. We try to set it in the context of the last week of Jesus, while moving around to the various Gospels and the canon of Scripture as a whole. This one–I think–had some particularly appropriate insights as we enter Holy Week heading towards Maundy Thursday and Good Friday. We hope you are as edified as we were. When Jesus entered Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, it was to the acclaim of the crowds. “Hosanna! Hosanna!” they cried. It must have been an inspiring sight to see for the disciples. “These people get it”, they must have thought. Now, finally, Jesus was getting the right recognition that he deserved. He is the coming King and his people have recognized it.

When Jesus entered Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, it was to the acclaim of the crowds. “Hosanna! Hosanna!” they cried. It must have been an inspiring sight to see for the disciples. “These people get it”, they must have thought. Now, finally, Jesus was getting the right recognition that he deserved. He is the coming King and his people have recognized it. Why the cross? Why this particular, bloody, grotesque means of execution? Why was this the necessary mode of the Savior’s redemption of the human race? Why not a life, leading into old age and peaceful death leading into resurrection? Why the seemingly Godforsaken horror of it all? This is the motivating question at the heart of Fleming Rutledge’s masterful tome

Why the cross? Why this particular, bloody, grotesque means of execution? Why was this the necessary mode of the Savior’s redemption of the human race? Why not a life, leading into old age and peaceful death leading into resurrection? Why the seemingly Godforsaken horror of it all? This is the motivating question at the heart of Fleming Rutledge’s masterful tome  I’ve already given something of a full review of Thomas Oord’s book

I’ve already given something of a full review of Thomas Oord’s book

After a number of months of having it on my to-do list, I finally got around to reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’

After a number of months of having it on my to-do list, I finally got around to reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’  And this is where I think about the book I’m reading for Lent,

And this is where I think about the book I’m reading for Lent,  Kierkegaard said that life can only be understood backward, but it must be lived forward. More popularly, “hindsight is 20/20.” I think there is no place this holds more truly than in the spiritual life. We’re finite beings, never more than marginally aware of the far-reaching impact upon the future of any single one of our choices. As Pascal said, if Cleopatra’s nose had been half an inch shorter, her fateful love affair with Mark Antony might never have happened, and the face of the ancient world might have been completely transformed.

Kierkegaard said that life can only be understood backward, but it must be lived forward. More popularly, “hindsight is 20/20.” I think there is no place this holds more truly than in the spiritual life. We’re finite beings, never more than marginally aware of the far-reaching impact upon the future of any single one of our choices. As Pascal said, if Cleopatra’s nose had been half an inch shorter, her fateful love affair with Mark Antony might never have happened, and the face of the ancient world might have been completely transformed.