My church is, across all departments, going through The Story, a chronological, abridged edition of the Bible that takes you through the story of Scripture from Genesis to the end of Acts in 31, novel-like chapters. It’s a fun project that’s challenging me to deal with narrative sections, teach large chunks at a clip, and point my kids to Christ throughout the whole redemptive-historical story-line of the text.

My church is, across all departments, going through The Story, a chronological, abridged edition of the Bible that takes you through the story of Scripture from Genesis to the end of Acts in 31, novel-like chapters. It’s a fun project that’s challenging me to deal with narrative sections, teach large chunks at a clip, and point my kids to Christ throughout the whole redemptive-historical story-line of the text.

That said, it seemed worth it to start posting my notes for these talks on a regular basis. It might happen every week, or not, depending on how helpful I think it is, or time constraints. My one request is that you remember these are pretty rough notes and I’m teaching my students, not a broader audience.

Text – Joshua 6 and the Invasion of Jericho

While a lot of us have trouble with most of what they read in the Old Testament, up until now a lot of us could get by okay. Let’s not play around here, though–there is a serious difficulty for many of us reading and understanding texts like this. The invasion and conquest of Canaan presents an assault on the modern mind, with modern sensitivities, horrified at what strikes us as a simple war of conquest in the name of God. We live in a post-9/11 world and the specter of religious terrorism, and not to mention modern ethnic cleansing, so this stuff understandably terrifies us.

Problem is, it seems like the Bible is full of awkward sections like this. What do we do with these pictures of violence? Or all the weird laws that we find in the Torah? How do we accept them as the word of God and possibly relate them to our own lives when they seem so terrible? We have to do something with them don’t we? This isn’t just an academic question for a lot of us. These are the texts that get thrown in our faces by our atheist and agnostic classmates when the Bible comes up. And, if we’re honest, they’re the ones that keep some of us up at night, doubting if what we’ve been taught in Sunday School is really all just a made-up, human construction.

What I want to do tonight is try to deal with this text, yes, but also the importance of reading the troubling texts of Scripture in context. In this case there are three contexts that I would tell you that you have to consider: historical, redemptive-historical, and the Gospel. But to set that up, let’s recap the story.

The Story Recap– At this point, the 40 years are up, and the Israelites are beginning to enter and take the promised Land. Joshua, Moses’ Second in Command, is now leading Israel’s armies and beginning to fight the Amalekites, and the rest of the Canaanite peoples, in order to take possession of it. That’s pretty much the story so far from last week.

1. Historical Context – So, here they are, about to take the ‘city’ of Jericho, and here’s where it becomes important to start examining the first context, the historical one, in order to understand what we’re reading.

a. Geopolitical-Theological Power Centers – Most of us, when we hear about a city like Jericho, make the mistake of thinking of a modern city, or maybe an old town, filled with normal life, families, etc. with Israel camping around, ready to invade. Here’s where modern archeology and biblical scholarship begins to shed some light. See, the reality is, most of the “cities” we see listed as being taken are really concentrated military/political/theological centers that controlled the regions.

They were small, maybe about the size of Trinity (our church campus). Realize, this is not LA or even Tustin we’re talking about. These were small, composed of maybe a couple hundred people which is why Israel can march around seven times in one day, and then still have the energy to conquer it. Beyond that, they consisted of military personnel, local royalty, slaves and prostitutes, with the civilian populations (if significant) living outside the walls. This was an attack on the equivalent of a key military base.

And here we come to something important: there is every reason to think that these civilian populations cleared out as the armies approached. There are a number of texts in the Law and in Exodus where God promises to “drive them out” before the Israelites:

I will send my terror in front of you, and will throw into confusion all the people against whom you shall come, and I will make all your enemies turn their backs to you. And I will send the pestilence in front of you, which shall drive out the Hivites, the Canaanites, and the Hittites from before you. I will not drive them out from before you in one year, or the land would become desolate and the wild animals would multiply against you. Little by little I will drive them out from before you, until you have increased and possess the land. –Exod 23:27-31

So, when Rahab talks about the “Fear” that had fallen on the land, there is the strong implication that most of any civilian population had cleared out before the Israelites ever got there. If they didn’t, before, then after 7 days of watching Israel marching around the gates, they did. These were not large massacres, but strategic strikes on key religious and political centers.

b. War Hyperbole and Rhetoric-– Beyond that, we need to address the language about total destruction in these texts right? Because we read these awkward phrases about “men and women and children”, “left no one breathing”, “left no survivors”, etc. According to Scholar Paul Copan we need to know that this is typical Ancient Near Eastern War Rhetoric:

This stereotypical ancient Near East language of “all” people describes attacks on what turn out to be military forts or garrisons containing combatants — not a general population that includes women and children. We have no archaeological evidence of civilian populations at Jericho or Ai (6:21; 8:25).8 The word “city [‘ir]” during this time in Canaan was where the (military) king, the army, and the priesthood resided. So for Joshua, mentioning “women” and “young and old” turns out to be stock ancient Near East language that he could have used even if “women” and “young and old” were not living there. The language of “all” (“men and women”) at Jericho and Ai is a “stereotypical expression for the destruction of all human life in the fort, presumably composed entirely of combatants.”9 The text does not require that “women” and “young and old” must have been in these cities — and this same situation could apply to Saul’s battling against the Amalekites.

So we have good reason to doubt that there was even close to the picture of families and dense, civilian populations here. And this is not an issue of the text lying either. This is typical ANE war rhetoric and most people would have heard and read it that way.

c. Infiltration as Well — This is backed up by the fact that If you look at the earlier sections of the Law, there are dozens of laws talking about not inter-marrying with people of the land, or later on in Judges, the Bible talks about fights with the Canaanites, that assume they weren’t all wiped out, but continued to be a significant presence in the land. Again, as we saw in this Exodus text, the strategy wasn’t coming in and actually totally wiping people out, but slowly infiltrating key power centers and moving into the land that way. This is not the indiscriminate wholesale slaughter that we might be tempted to picture.

These and a number of other historical factors need to be considered when reading these texts. We live at a distance of thousands of years from these text and bring assumptions to it that the original readers wouldn’t have shared, and don’t assume things that they would have. So whenever you run across a difficult text in the OT, realize that there are a times when a lot of confusion and heart-ache can be avoided with a good commentary and some historical scholarship. Not entirely, of course, but still significant.

2. Redemptive-Historical Context – That said, the historical context isn’t the only one to consider. Another level that we have to consider is the “Redemptive-historical” context–or the whole story of the Bible. These events take their place in a longer story and must be understood within that context or they don’t make sense.

a. God’s patient judgment – One angle on this is to consider why God says he is driving out the Canaanites. Back in Genesis 15:13-16 God says:

Then the Lord said to Abram, “Know for certain that your offspring will be sojourners in a land that is not theirs and will be servants there, and they will be afflicted for four hundred years. But I will bring judgment on the nation that they serve, and afterward they shall come out with great possessions. As for you, you shall go to your fathers in peace; you shall be buried in a good old age. And they shall come back here in the fourth generation, for the iniquity of the Amorites is not yet complete.”

Then again, we read in Deuteronomy 9:4-5:

“Do not say in your heart, after the Lord your God has thrust them out before you, ‘It is because of my righteousness that the Lord has brought me in to possess this land,’ whereas it is because of the wickedness of these nations that the Lord is driving them out before you. Not because of your righteousness or the uprightness of your heart are you going in to possess their land, but because of the wickedness of these nations the Lord your God is driving them out from before you, and that he may confirm the word that the Lord swore to your fathers, to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob.”

In these texts we see that God was using the Israelites as his sword of judgment. This is not God just looking around at random and destroying a people. The cultures that were invaded were abysmally dark, notorious for their rampant injustices towards the weak and the poor. They were conquerors and bloody bullies who soaked the land in blood and death. These are not peaceful monasteries in Tibet we’re talking about here. Their worship was corrupted to the point that it involved bestiality, temple prostitution (which like involved sex-slavery), and, most horrifying of all, child sacrifice. We have archeological digs with pits, full of the skulls of children these cultures offered up to the flame. As an associate of mine pointed out, just consider Rahab the prostitute–how weird is it that she was willing for invaders to come? No, for her, and those like her, this was not just invasion, but in many ways, liberation.

See, God tells us that he is the God who care about poor, powerless, etc. He cannot and will not let injustice go on forever and so, at times, his final judgment breaks out in the present in order to stop gross injustice. Beyond that, in the first text we see that God waited 400+ years for the people to become corrupt enough to justify thing. He didn’t just pick a land and take it, he waited until the culture became so corrupt and wicked that their judgment was merited and necessary. This was God’s extreme patience towards the Canaanites–he waits hundreds of years for their sin to ripen and mature (far longer than we probably would have), until even God’s patient mercy must give way to judgment.

b. God will give them no taste for conquest — The other thing we need to note is that this is not a set-up for empire-building. In Deuteronomy he commands them not to have standing armies, chariots, or any of the other paraphernalia of empires. This a limited project, undertaken at one time, for a specific purpose. This is not a program of Empire to be appropriated later, or used to justify other violence. “You get this land, about half the size of California and no more.” This is part of the logic of the total destruction of these key sites. Israel is not to get a taste for war. And you see in the rest of the OT, the rest of the Yahweh-approved wars are fought defensively.

c. God’s other purpose is to create a Redemptive Space — The second reason that needs to be considered is what were God’s purposes with Israel. God had project: he wanted to create a people through whom the world would see what God was like. What’s more, the ultimate goal is not for Israel alone, but that all the nations of the world may be saved and blessed by God through Israel in the coming of her Messiah. For this to happen, Israel needed a land, a space to develop a culture as a people, set apart from other peoples, for the redemption of all peoples. They needed space to practice the 10 commandments. A set-apart, holy land devoted to justice, peace, and the true worship of God, in a way that would be un-corrupted by the local Canaanites and their distorted practices.

This is another, if not the key reason to understand that this was not a whole-sale killing, genocide or ethnic-cleansing. Israel took Rahab and her family in as they acknowledged the true God, and as a friend pointed out, this is likely just a shadow of Israel’s mercy to other people–the accounts don’t cover everything. Just as they included repentant Egyptians in the crowd as they left Egypt, it is not unlikely that repentant Canaanites could join the people. Of course, this points ahead to the Gospel of Jesus and the inclusion of the Gentiles. Clearing out the nations serves the purpose of one day bringing in the nations.

So what we’re seeing then, is a tactical, limited invasion, whose goal was to establish beach-heads, driving out the surrounding peoples and their corrupt cultures slowly. Why? For God’s specific, purposes of judgment on a wicked people, and the grand redemptive purpose of saving all peoples. (Incidentally, this is why this can’t be used as a warrant for modern violence–different covenant, no divine command, etc.)

This is where I make an analogy that might not work. Most of us look back at WW2 and think there was a lot of horrible stuff that happened on both sides. I mean, I think I’m only now reconciling myself to the horror of the firebombing of Dresden and the terror of Hiroshima. These were…damnable. Thing is, with all of Europe in the choke-hold of a monster, and the gaping jaws of Auschwitz and the camps devouring millions of Jews, I don’t think any of us would say that no bullets should have been fired or that no bombs ought to have been dropped.

If that holds true for the temporal salvation of some people and one point in history, how much more then for the salvation of the whole world? Again, this may not work for you. I get that. I’m not sure it does entirely for me either. Still, it might put the breaks on our rush to rule this out as something God “couldn’t” do. We have a God who has committed to saving historical beings, precisely in history. We shouldn’t be surprised if that involves some messy moments.

3. Theological Context of Christ – Of course, the final context I would say we need to look at this in, is the Gospel of Jesus Christ. On the one hand, you can’t understand Jesus without the rest of the story of the Bible. On the other, you can’t understand the story of the Bible without look at the Gospel of Jesus. The life, death, and resurrection of Jesus are like a light at the center of the Story-line that allows us to see all things properly in its light.

In this case, I think the Gospel reminds us of a couple of big-picture theological truths that we need to keep in mind when we look at these stories.

God Hates Sin – One thing these texts remind us of is the radical seriousness with which God takes sin. I was talking to a buddy the other day and he was telling me how it just really occurred to him that God hates sin–like, he really can’t stand it to the core of his being. But honestly, that’s a good thing, right? If God is good, loving, just, great, righteous, and holy, he really can’t love sin. He can’t and shouldn’t put up with it forever, right? I mean oppressing the poor has to end sometime right? Violence, arrogance, racism, rape, child-sacrifice, sex-slave trade, and idolatry can’t go on forever. And we don’t want it to.

This is what we see in the Cross of Jesus. The cross of Jesus is God judging sin for what it is–something damnable and horrifying–something that has not place in God’s world and will ultimately be done away with. What happened to Jesus is what ought to happen to us, and will, if we don’t allow him to be judged in our place.

God Loves Sinners – Now, while that’s one truth we need to see, there’s a far deeper one beneath it that is essential for us to consider–God loves sinners:

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly. For one will scarcely die for a righteous person—though perhaps for a good person one would dare even to die—but God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us. Since, therefore, we have now been justified by his blood, much more shall we be saved by him from the wrath of God. For if while we were enemies we were reconciled to God by the death of his Son, much more, now that we are reconciled, shall we be saved by his life. (Romans 5:6-10, ESV)

The fundamental truth about God that we see in the Cross and resurrection of Jesus Christ is that his will is to save them. He loves them. He doesn’t want to judge us. He doesn’t want to ultimately condemn us. He is just, so if we refuse to turn, if we continue to hate good and choose evil, well, he’ll let us do that and suffer the consequence. But his deep desire is to draw us to himself. He looks at us and says, “Though I can’t stand what you’ve done, both to me, your neighbor, and yourself, yet I love you. I would separate you from your guilt. I would remove from you your sin, that I might hold you to my own heart that loves you still.”

So in order to do that, he suffers judgment himself. Realize, the God we see in the OT, is the same God who was willing to become a man and suffer the worst pain that anyone in human history has ever faced. This is the God who suffers the rejection of Hell for us, so that we might not face it. In the end, God conquers sinners through judgment–His own, on the Cross. This is ultimately what I have to look to.

We’ve gone through a lot of these different contextual issues and historical considerations that change the shape of how we think about these text. They’re important to consider and helpful as we wrestle with the awkwardness of the story of scripture. At the end of the day, though, I have to put my trust in that God is who I see in Jesus Christ and him crucified–the God who proved himself perfectly just and perfectly loving in a way I could have never imagined. I never could have fathomed a God so good he was willing to die for those who wanted to put him to death in order to save them from death.

So when I come to these troubling texts, no, I don’t just read them and say, “Welp, it’s the Bible, so, no problem here.” I have doubts and struggles. What I do say is, “God, you’ve already proven yourself to be unfathomably just and unfathomably loving beyond my finite and fallen comprehension. I still don’t have a grid for the Gospel. I’m having trouble accepting this, but I trust you, so shine a light on this.” Then I wait. I study, pray, and wait. And you know what? I think God’s okay with that.

If you’re struggling tonight, that’s okay. Church is meant to be a place where, yes, we confess, praise, trust, and grow. It also should be a place where you can safely struggle. What I do hope you’ve seen is that when it comes to difficult texts, context matters–a lot. And can make a big difference. So before you chuck your Bible across the room, slow down, ask questions, do a little digging and prayer and trust God to show up.

Soli Deo Gloria

Okay, so, I know this is an incomplete treatment of the text, or even the whole conquest. I didn’t address God’s rights as creator, scratch the surface of the epistemological issues, moral grounding, and the authority of scripture over culture. Honestly, I had a half hour, and I try not to push my students beyond that. For those who are interested in exploring the question in greater depth, I would commend these resources to you:

1. Is God a Moral Monster? by Paul Copan – This has three chapters devoted to the question of the context that are extremely helpful on this question.

2. How Could God Order the Killing of the Canaanites? by Paul Copan – Short article summarizing much of the book.

3. Is YHWH a War Criminal? by Alastair Roberts — Another thoughtful, article-length treatment of the subject.

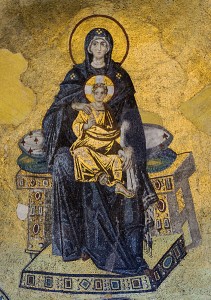

Popular Science wants you to know that a human virgin birth (or, more properly ‘virginal conception’, not ‘immaculate conception’, which is something entirely different) is pretty impossible. While “parthenogenesis” has been known to happen in non-mammalian species, there are a couple of obstacles to that happening for us:

Popular Science wants you to know that a human virgin birth (or, more properly ‘virginal conception’, not ‘immaculate conception’, which is something entirely different) is pretty impossible. While “parthenogenesis” has been known to happen in non-mammalian species, there are a couple of obstacles to that happening for us: